tv Book TV CSPAN January 28, 2013 1:00am-2:00am EST

1:00 am

1:01 am

an event -- he was in many ways unprepared for. he wandered down to richmond, virginia's slave auction rooms, and there beheld an auction of humans for the first time, and he became captivated by this subject and painted a number of images and published a number of drawings in the illustrated london news in order to help raise awareness about american slavery. >> host: was he an abolitionist? >> guest: i suspect when he first came to america he was aware of the antislavery movement and would have described himself as being opposed to slavery. but after coming here and witnessing american slavery and witnessing the slave auctions, he then later described himself as an abolitionist. he was not a politically active abolitionist. it was not that he was member of any of these many organizations

1:02 am

that existed in britain even after the end of british slavery, but he was writing and publishing images that in many ways were as important as the activism of those who were politically involved. >> host: why did he come to the states? >> guest: it's one of those fun little stories of the 19th 19th century. the british novelist, william thinker where, who was second only to charles dickens in popularity. wonderfully loved by americans, was on a six-month speaking tour, and eric crow's father was a good friend of zachary's, and so he invited his best friend roz younger son to come along and serve as his traveling secretary but eric crow was already a very highly trained artist, in his early 20s. so as he went around with satchry, traveling up and down the eastern seaboard, he made

1:03 am

reservations and he traveled with satchry and made sure everything was taken care of. but he also sketched the whole way he was traveling. and he and zachary differed quite significantly on their impression of slavery in america. zachary decided he would not speak publicly on the topic because ten years earlier charles dick dick 's had come to america and famously pretty much excoriated americans about slavery, and in his book on notes on america, he had a whole chapter against slavery, and it hurt his sales in america after that. so satchry remains mum on the topic. >> host: for commercial reasons. >> guest: yes. but in his letters you also get a sense that he was pretty

1:04 am

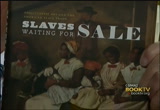

patrician and did not see that as all that bad. >> host: what is this painting on the front of your book? this painting is the culminating statement that eric crow made against american slavery. its title was slaves waiting for sale, richmond, virginia, and it was exhibited at the royal academy in 1861. and that alone is a remarkable thing. the world academy, the premiere institution for exhibiting works of art in the 19th century, english-speaking world, wasn't typically a political institution. most of the works of art that were accepted for exhibition were expected to not be too extreme in one way or another. don't go too far about a social statement. don't be too far in being artistically innovative. you had to find a middle line in order to be accepted. and there had been very few

1:05 am

pictures exhibited at the royal academy that had -- that featured people of african descent. there will some of the preceding couple of decades but not many at all. this was not just a picture featuring somebody of african descent. it was a clearly political statement opposed to american slavery. and in one of those rather amazing coincidences of history, the exhibition opened may 7, 1861, and the first shots had just been fired or fort sumter a few weeks previously. when the exhibition opened in may, all of london was atwitter about the war in the u.s., and of course all of london was talking about what role should the united kingdom take in the american war. there were many in britain, very much in favor of supporting the

1:06 am

confederate states of america because of the amount of money that britain made from american cotton. there were, of course, many opposed to that as intel we all know that ultimately britain remained neutrality but on that moment on may 7, 1861, no one really knew what would happen. >> host: were there slaves in great britain at that time. no slavery had been abolished in britain its colonies officially in 1838ment so it had been a long time since britain had been directly involved with slavery. but britain was really the place where antislavery movements gap and they remain quite involved after the end of british slave russian trying to end the rest of world slavery. and the u.s. slavery was not the end of slavery in the world either. it continued in brazil and cuba, until long after american slavery ended. >> host: professor mcinis, as

1:07 am

an art historian, walk us through this painting on the front of the book. >> guest: what i try to do in the book is do exactly that. walk viewers through the painting, reconstruct the material world of the american slave trade that eric crow would have seen when he visited the richmond slave rooms in 1853. and i try to reconstruct what the experience would have been for african-americans caught up in the trade. in the decades between 1820 and 1860, it is estimated that more than 350,000 slaves were sold from the upper south, taken away from their families and those they loved, and sent hundreds if not thousands of miles away to the booming cotton south, alabama, mississippi, louisiana. this book tries to tell the story out that experience for those individuals. what i was able to do, and what

1:08 am

is really kind of fun, i think, about the book is readers can go on a journey with eric crow, studying at the hotel where he stayed in richmond, where he woke up that morning, picked up richmond newspapers and was astonished to see advertised there in the upper corner, people for sale. it was something he had never experienced before. richmond was the first southern city he visited. >> host: is that what got him to go to the walk to selma. >> guest: he was prime for that. when he was in new york city he bought a copy of harriet beecher stowe's uncle tom's cabin that had just been released in 1852, and he read the novel and was harrowed by its contents. its horrified him, this story of american slavery, and he was particularly attracted to the slave trade. the commercial aspect of

1:09 am

slavery. the selling of humans, one to another. and he was determined when he got a southern city to witness this aspect of slavery himself. so on the first morning he opens the newspaper at his hotel and seize several advertisements for the auction of slaves. and he asks somebody working at the hotel who was probably an enslaved man himself, where these sales were located. they were just a few blocks from his hotel, just a few blocks away from thomas jefferson's virginia state capitol building. this great symbolic image of representational democracy and three blocks away people were being sold, day in and day out, every day, six days a week, 52 weeks a year, thousands of people annually sold from richmond, most of whom were then sent to places south. so, the reader can go on that same journey with crow. i did research on deeds and

1:10 am

commercial direct yoris and -- directors to understand which businesses he would have walked past and where the slave trade took place and where it was in recommendation to the city's other businesses, industries, retail establishments, churches, civic institutions and its state buildings. none of them are very far removed and yet the slave trade was tucked away in richmond. it was not a district you would good to unless you had reason to go there. >> host: why is that? >> guest: it was not a part of richmond's commerce. they weren't ashamed but also not particularly proud. virginia's slave economy was not a growing economy. it was a stagnating economy. virginia's agricultural economy was not a growing economy. but a stagnating one. and the reason why so many slaves were sold out of the upper south to the lower south is because in many ways there

1:11 am

weren't new slaves needed in virginia and maryland and north carolina, where they were needed were in the new cotton lands of the southwest, and so an owner quite often might have what he considered excess capacity, and so he would sell off one or two slaves here. almost always breaking up families, because what sold and brought money in the market place were people aged 15 to 30 years. and so that usually meant breaking up families. husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers and their children. and they would be sent to richmond, which was a bit of a gathering place, and most of the slaves purchased in richmond were purchased not by slave owners but by other slave traders. so then would take them hundreds of miles away, either marching them overland where the men would be chained together two-by-two, the women usually not chained and marching at the back of the group. and sometimes they would walk as

1:12 am

far as from richmond to new orleans. and when the system grew more complete it was more common for slaves to be sent by railroad and then sole again in new orleans, to slave owners, usually, at that point, and then put to work in the cotton and sugar fields. >> host: what was the going price? >> guest: the going price varied and continued to increase, and one of the things that we know is there was a market that divided people into categories. and so a number of dealers had these things they called price sheets, and these price sheets listed categories, prime men, number one men, boys, 4'3" and above, boy, 4'0" and above. and similar categories for women. and the prices varied. most prime were male field hands, usually ages 15 to 30.

1:13 am

older slaves or younger slaves going for less. but you could imagine a sort of going rate on average of a thousand dollars or less for most of the 1850s. >> host: eric crow, how did he -- did he stay in place for this? >> guest: there's this great story that goes along with this painting that we both know -- we know from two sources, crow's account of the event and also a young new yorker who happened to be in the same slave room. crow tells the story of walking into the first auction room and being stunned by what he saw. his senses were assailed. the smells, sights, up sos, the emotion of the slaves he witnessed. they were being sold away. and he just stood there in silence, stunned, and moved on to the second room. then the third auction room. and there he sees a group of slaves before the sale. seated on benches off the side

1:14 am

of the room, awaiting their fates and not knowing what they're fates were, and as he writes he was moved by this group of individuals, so moved in fact that he snatched houston pen and paper and began making the sketch you see there. and as he was first making the scene, everybody was kind of interested in what he was doing, and they crowded around him. and at that time the sale was supposed to commence. auctioneer was on the block, trying to get attention nor the sale, and the audience is much more interested in what crow is doing. and so the sale does not proceed, and the auctioneer comes up to and asks crow, what are you about? and crow says, i am sketching. so the auctioneer tries again and is not able to attract the attention of the audience. another question, another somewhat snappy remark from crow and the auctioneer returns. and by the third team the

1:15 am

auctioneer is so angry that crow realizes he better get out of there so he leads the auction room and hides in another room. hoping that they will forget bat him. when he leaves that room he sees the entire audience, the auctioneer and all the people in the slave auction room coming to get him, because he knew he was an abolitionity. a young new yorker publishes an account of this in a newark newspaper later, writing about the same tale of an artist. at first everybody very interested until they realize what he is sketching. and you would not sketch a slave auction unless you were opposed to slavery, unless you were an abolitionist, and he, too was surprised that crow was able to get away without harm. >> host: what other slave markets did eric crow visit. >> guest: the only other major southern city he went to were two. charleston and savannah.

1:16 am

in charleston, the slave auction and the slave trade occupied a very different place. it was a much more public thing. south carolina was certainly one of the most pro slavery states in the union, and that was really gathered in charleston. many pro slavery authors coming from south carolina and charleston, and they were very public about their slave trade. it took place in one of the largest open squares in the city, right in the center of their commercial district. >> host: is it considered an activity for families to attend? cincinnati was a spectacle, daily spectacle. every day at 11:00 a.m., near what we today would call the colonial exchange building in charleston, right at the foot of broad street, what was then the post office, a major gathering place. every day at 11:00 a.m. all the auctions took place, and so slave traders would bring their slaves there for auction before

1:17 am

taking them back to the buildings in which they were held, and they were held out in charleston until 1856 when a city ordinance moved them indoors, not because they were ashamed of the slade trading activity but because it was blocking traffic and interfering with commercial enter prize. >> host: did eric crow become a well-known painter in the states because of this original painting and then other paintings? >> guest: actually, not at all. eric crow's work was known in britain. his painting is exhibited in the royal academy. his published -- publications of images and drawings were published in the illustrated london news, which was widely read here by the sort of elite intellectuals but would not have been broadly known. this was a topic that could not have been exhibited in an american exhibition hall in the period of slavery. >> host: even in the north. >> guest: even in the north.

1:18 am

you think of new york at the time of the outbreak of the civil war, there's still a very strong pro southern fragment in new york, because of the amount of money that new york is making from the u.s. cotton trade, and there are many southern sympathizers in the city of new york. maybe in boston where abolitionists have its heart, maybe you could have exhibited something similar to that there but it would have been a very difficult thing. and artists had to worry about their market, and american artists did not paint a subject as difficult as this. they rarely even touched upon the subject of slavery prior to the civil war, because they did not wish to offend what they would have described as their southern customer. >> host: did there become a genre of abolitionist art? there is an enormous amount of abolitionist imagery. and my book tries to trace a particular story of talking about how an abolitionist

1:19 am

imagery, re get to the topic of the slave auction. because by the 1850s it was the new subject in antislavery imagery. the most famous antislavery -- the earliest image is one that shows the international slave trade. it was an image produced in britain in 1797, that shows the plans and sections of the slave ship where hundreds of african bodies next to each other that were trying to demonstrate the horrors of the international slave trade and that image is very much an eye cop yoke -- eye con graphic image today. and i tried to trade that image which talk about the trade, that dealt with people anonymously. there were hundreds of identical bodies lying next to each other in the ship. by the time we get to eric crow you have a focus on people who

1:20 am

have emotions and who are part of families that are being broken apart. and there's a long evolution of imagery in between that is that movement from treating slaves as anonymous individuals to really thinking about the impact on people. what's really radical about crow's image and why it attracted the attention of critics, even though he was a young and unknown artist, was because it was a new image. it didn't show the theater of the auction that had become quite common by the 1850s. it wasn't the auctioneer on the suction block, with his hand raised above his head and a gavel in his handand the theater of going, going, gone, which became quite well-known and rehearsed. and because it was so well-known and rehearse in many ways locellate of its meaning. what crow does is shift that moment to the moment before the auction, to the moment when people are sitting there,

1:21 am

pondering their fates, pondering what awaits them. and its that emotional impact he is able to put forth in that painting that brought it to the attention of critics. >> host: professor, when for the first time were eric crow's paintings displayed in the u.s.? >> guest: 20th century. this painting history is unknown, from its last known exhibition in 1861, until it was sold to an american collector in the 1950s. we don't know what happened it to in between. it was obviously in multiple people's collections, passing through hands, but not something that was terribly well known. definitely a picture of the moment. and that is true of a lot of slavery imagery. once slavery ended, there was a diminished interest in the subject. >> host: who is it sold to in the 50s and who owns it today. >> guest: it is owned by teresa hines, kerrer, her former husband, senator hines, was a

1:22 am

major collector of american arts and the family has very important collection, including this picture. >> host: do you know who bought it in the 50s no the hines heinz family. >> host: what drew teach here. >> guest: i teach a range of classes in art history everything from a rare traditional survey from the renaissance the present to more specialized classic on american art and material culture. >> host: you're an art historian. we have been talking about slavery. what can we learn through the study of art. >> guest: what we can learn are multiple things and this book tries to tell those two stories. one of those stories is the role in which images are received, to understand both the background that informs those images and then to understand the impact those images had on others. throughout the antislavery movement, images play major role in shaping the way people

1:23 am

understood antislavery sentiment. pamphlets can be published. books can be written. sometimes it's that singular image that makes an abstract concept a very personal one and a very individual one, and we find throughout the history of abolitionism that images move the conversation in important ways in the same way that works of fiction do as well. uncle tom's cabin had an enormous impact on the santa alivery movement in the way that decades of writing pamphlets about the horrors of american slavery had not yet reached the right audience, but with the combination of uncle tom's cabin, which is ilustrate, and it's that combination of telling stories stories and stilling stories through pictures that helped spread antislavery sentiments to a much wider audience. >> host: when did photography, become an issue, given the

1:24 am

subject, slavery and abolitionist. >> guest: only begins to play a role in the u.s. civil war. as federal troops begin to occupy southern cities, it was not at all uncommon for them to photograph sites of slave auctions, although not as many as i wish they have because those are mostly lost from us, or photographing other things related to the history of slavery. but they more often were photographing things related specifically to the war. so that evidence is quite scant. >> host: if people are interested in seeing some of the abolitionist art, where would you recommend they go. >> guest: there's an enormous amount of it online. the vast majority of the antislavery imagery was produced for publications, produced for antislavery almanacs, antislavery pamphlets, for books published by former slaves

1:25 am

written before the civil war. almost all of those works are illustrated works, and whether it's in google books or a variety of libraries that are digitizing their 19th century collections, a lot of that work is available online and if you just do a simple google search of abolitionist imagery, hundreds of images will come up. >> host: what about a museum if somebody wants to see the real piece? >> guest: this painting still in private hands and is not daily on public view. i am working on an exhibition to be held with the library of virginia in 2014, that is, at least the working title is "to be sold: virginia and the american slave trade." and we are certainly quite hopeful we'll have that painting by eric crow as well as the other surviving painting by eric crow on american slavery, both at the exhibition. and so that would be in richmond at the library of virginia in

1:26 am

2014. a long way awesome the other surviving eric crow paining owned by the chicago history museum that collected rather broadly in materials related to the civil war because of their interest in lincoln in part, and in part because in the period after the civil war, in chicago there was an exhibition, u.s. civil war museum that exhibited dozens, hundreds of artifacts collected throughout the mesh south at the end of the war to tell the story of the civil war, and obviously one of the most important chapters of that story is telling the story of u.s. slavery. >> host: two surviving eric crow painings? >> guest: of slavery there are dozens of eric crow paintings in britain. but other than this brief period from his trip in 1853 to 1861 when he painted this, his last picture, on u.s. slavery, in that span he painted a number of works, most of which are now lost. and after that he returned to

1:27 am

his bread and butter, painting british literary historical scenes, scenes of dragonsons and shakespeare and speak like that. >> host: have you seen either of those two surviving painings. >> guest: yes, i've spent a lot of time with them. @as an art historian, i work on the work of art. it's a text that tells us much. it's in studying the details of the paints that you again to ask questions such as, the clothes they're wearing and wondering, is that what way that are wearing on that day and with more documentary research, being able to learn that in fact, yes, slaves were dressed for sale, dressed very well for sale, in order to wire away the harshness and brutality of their life histories and to make them seem more appealing to potential buyers. it's looking closely at the painting you notice things like

1:28 am

the grebe ribbon that the young boy in the painting is grasping in his hand. there's no real explanation for the green ribbon in the painting. there's no woman in that image wearing green ribbon so i speculate it might bell the green ribbon he took from his mother or sister as a memory of that individual, because of course now being wrap up in the american slave trade he knows it's likely he will never see that p. again. so close examination of the picture, asking questions, and then seeing what you can do to answer those questions that pictures raise. >> host: what do you see in the actual painting that we don't see here in the reproduction on the cover of your book. >> the cover of the book leaves out a significant portion of the painting. so there are kind of two sides that extend beyond. the book is tall, the painting is wide so doesn't fit on the cover. on the right-hand side is a male slave, seated all alone, and

1:29 am

what is so remarkable about the image of that male slave is he is not depicted as decades of men of african descent have been depicted. he is not happy, he is not sitting there with christian resignation, awaiting his fate as uncle tom did throughout the story of stowe's uncle tom's cabin. he is angry. his fists are clenched. his arms are wrapped. he is leaning forward. the look on his face is clearly sullen, angry, and the critics noticed that. there had never been before an angry man of african descent on the walls of the royal academy. and that was crow's political radicalness. that little bit of true abolitionism coming out because he was a slave who coot coo at any moment rebel, run away, and resist with force if necessary.

1:30 am

so that very important detail unfortunately does not fit on the cover of the book. then on the left-hand side are white men, entering into the room of the slave auction, and they are potential buyers, and they are of different types. they probably represent a slave trader and maybe some slave owner purchasing for himself. and so they complete that story that eric crow was trying to tell, of the uncertain fate that awaits not only these individuals seated in this richmond sales room on this one day in richmond, but the thousands who passed through there annually and the hundreds of thousands who passed through the slave trade over the decades in the american south, and in its own way, by not answering that question, by not giving us resolution, we don't know what

1:31 am

state these -- what fate these people with face. at that moment in 1861 when it was being exhibited in london, nobody knew the fate of that war, either, and nobody knew the fate of britain's involvement in that war. it was really a picture that perfectly captured this moment of uncertainty for everybody involved. >> host: who are some of the other abolitionist artists people should be aware of? is there are very few. most artists stayed away from such political topics. turner, famously exhibited a painting that we know in short as the slave ship in the royal academy in 1840. and it is the work that today i think most captures the anguish and pain of the international slave trade. it shows a very small ship on a storm-tossed sea, and the leg of one slave sticking up with a

1:32 am

shackle still on it, and lots of fish swimming around. it was clear the slave had been thrown overboard and the slave is being consumed by the fish and or sharks in the sea. but it strikes a very modern tone because it is not didacted in its content. it allows the emotion of paint brush, brushwork, and color, to tell its story. instead of the more narrative approach that somebody like eric crow tookment one that was very much in accordance with 19th 19th century victorian story-telling. very different from the more modern since -- sensibility of turner. >> host: you have another picture of a couple of african-american male slaves escaping attacking dogs. >> guest: yes. that picture was painted by

1:33 am

richmond endsdale. he was a very famous what they called in britain animal artist. he mostly painted animals. dogs, horses, steer, stags, et cetera. and this painting is really the only one he did that touched on the topic of slavery. what he shows are two slaves running away in a swamp. they're being chased by very large dogs. the swamp has made very swampy by the very obvious inclusion of a nick in the foregroup and it was exhibited at that same 1861 exhibition, and so you have this great moment where you can compare the response of critics to these two paintings, and they talk about oboth of them, given the timing of the opening of the u.s. civil war, and they very much preferred crow's paintings.

1:34 am

they described deal's painting as a, quote, bit of studio romance. they knew that crow had been to america. crow was very well known in the british arts establishment. he published as a journalist, they knew from that it was a small world, they all knew each other. they knew he had been in america. so they saw in his work truth. and endsdale had never been to the u.s. or witnessed slavery. so they saw his work as more dramatic and, as they say, bit of studio romance. it's a beautiful picture two versions of it. one of them owned by the liverpool museum, and liverpool played such an important role in the international slave trade, that they have a museum about slavery in liverpool, and so that painting is there, and then a second version alsohand by endsdale was purchased by the new smithsonian museum of african-american museum hoist

1:35 am

and culture, so i assume when the museum is open that painting will be on view in washington. >> host: it's a couple, not two african-american males. when did you get interested in this topic? >> guest: i've long written been the history of the american south in the 18th and 19th 19th century. i teach here at the university of virginia where that history is all around us, and i have long been teaching about subjects that relate to slavery. i've been teaching this painting by eric crow for years, and have always been intrigued by it, thinking that there is a story there, waiting for us to rediscover it. so it's a project i began working thon 2006 and the book recently came out.

1:36 am

>> kenneth mac is the author of the new book, representing the race, the creation of the civil right lawyer. tell me about your book. >> guest: my book is a collective pieing agraph of six african-american civil rights lawyers who practiced law during the era of segregation and it's about their struggles with civil rights and racial identity. at it about the fact that to be an african-american civil rights lawyer in this era, argue in the book, is to be caught between the black and who it world. both blacks and whites want things of these lawyers and identify with these lawyers. so, to be this kind of a lawyer, thurgood marshall and people

1:37 am

like him, was not just an african-american lawyer but member caught between the black and white world. >> host: how difficult for an african-american to become a lawyer at that time. >> guest: it's not difficult to become a lawyer. you have to good to law school like everybody everybody else, which does cost money, but it's difficult to be a lawyer because no african-american lawyer in this period is going to have white clients or very few of them will have white clients. most black people don't have money and if you have money and you're black, you hire a white lawyer, because white lawyers will be more effective in a segregated society. so very difficult to succeed as a black lawyer, even though it's not difficult to become a black lawyer. >> host: why these six men? >> guest: they are -- have something in common. they're all one generation. they all were the foot soldiers, as you will -- the legal arm of the civil rights movement.

1:38 am

1:40 am

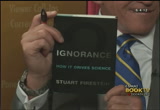

>> now stuart firesteen talks about his book, ignorance. how it drives science. >> host: how many brain cells do we have. >> guest: we used to think a hundred billion. that number hung around for ages, in all the text books but a couple of years ago a young neuroanatomist sent an e-mail around asking how many brain cells we had and where we got that number from. and everybody wrote back 100 bill and others wrote back i have no idea. so she developed a new method of counting brain cells. actually not a trivial problem

1:41 am

to count brain cells, self tens of billions. so she developed a new method, very interesting, and she recounted them and found there were in fact only 80 billion. now, that's an order of magnitude, okay so not that big a difference. at the larger difference might have been we thought we had ten times as men so-called glialy cells, the nonbrain parts of the brain that put it together. and we thought we had ten times as many and we only have 80 billion of the gleal cells. so in one fell swoop we lost 120 million cells in the brain. >> host: what don't we know? >> guest: well, that's an awfully big question. as i point out, ignorance is a much bigger question. i think the question is not only what don't we know but what don't we know that we don't

1:42 am

know? >> host: donald resumes field. >> guest: you got to that before i did. there it is. he was actually correct saying that, although he 'sounded bee if you hadled when he did because he was worried about a war that wasn't going so well. but that's a good question. there are limits to our ignorance? because that's more important than the limit to our knowledge. >> host: you say in your book that when you get together with other scientists you talk about things you don't know rather than what you do know. >> guest: sure. my favorite quo is from marie currie, who upon gaping her second graduate degree wrote a letter to her brother that said something the effect of one never notices what has didn't done, only cares about what remains to be done, and that gets us into the lab in the morning and keeps us there late at night and moves us alone. we don't care about what everybody knows.

1:43 am

now let's get to what we don't know. what do we need to know. what would be the next best thing to know, so forth. >> host: page 28 of ignorance. george bernard shaw in a toast at a dinner setting, albert einstein proclaimed science is always wrong. it never solves a problem without creating ten more. >> guest: i think i say, isn't that glorious? >> host: you do. >> guest: i think that's exactly the right description of science. i should say i believe george marshal -- just to name drop a little bit, who years before that had come up with this idea of question propagation, the principle of question propagation, that every answer begets more questions. >> host: do scientists wrest on their laurels after a while. >> guest: i guess everybody does after some point. i think resting on laurels is a dangerous thing for science to do because those laurels tent not to be all that foundational,

1:44 am

all that strong a foundation. i think one of the thing that probably the public recognizes least about science is that we tend to have less regard for fact than i think is generally thought to be the case. scientists, although we work for facts, we work to get data, we also realize they're the most mallable, least rely part office the whole operation. that whatever you fine today will superly be superseded in some way or another, revised, overturned completely in the worst days but certainly revised by the next generation of scientists with the next generation of tools. it's always been in the past 400 years or 14 generations. and i think we welcome it. science is revision. we welcome revision. revision and signs is a victory. >> host: you right in here that science and nature magazines are very important for scientists to get published in, but if you are going to recommend to your students to read those, you'd

1:45 am

recommend not reading last issue but ten years ago. >> guest: yes. i think they should read this issue, too, to stay current. but quite often the graduates come rushing into the lab with this week's nature which has some great set of experiments suggesting that, i can see what the next experiment is. let's get to work on this and get our nature paper. and i know that peep who wrote that paper have luhr done the next ten experiments or thought of them, and that the real place to go often for ignorance, for good ignorance, high quality ignorance, were the papers published ten or 15 years ago in nature. the leading papers of the derrick but which couldn't have asked certain questions because we didn't know them to ask yet. they didn't have the technology or the tools developed in the last few years so they're ripe be revisited. >> host: has technology helped in discovering science? >> guest: sure. technology is a critical part of the whole arrangement. this is often science drives --

1:46 am

science questions drive technology, and technology then goes ahead and drives science. so, instrumentation has always been a critical part of science, since galileo and the telescope began it 400 some odd years ago. >> host: besides the number of brain cells, professor, what's another fact that we knew that has changed. >> guest: a bunch of those mitchell favorite one, because my laboratory happens to research taste and smell, the senses of taste and smell so we work on what are called the chemical senses one of the best known facts -- the so-called taste map which you'll find in every high school and college and medical school textbook and most people believe that there's a map of sensitivity on your tongue, and that you taste sweet things with the tip of your tongue and sweet and sour things on the side and bitter in the back, and this is completely untrue. it's a mistranslation of an

1:47 am

anecdotal report by a german physiology professor in the 1900s which was picked up by a well-known college professor in the 1940s, whose name is boring. you can imagine it is a joke for many generations. but he put this in his book as if it were a complete fact apparently it was mistransmission just stood the test of time somehow or other even though it's totally wrong. >> host: what has stood the test of time. >> guest: some three, four, five hundred years ago. >> guest: so maybe thing does but maybe not in their original form. certainly newton has stood the test of time. newton continues to work, we can launch space shuttles and build bridges and this sort of thing uses newton's laws of gravity and force but they've been revise significantly, most

1:48 am

notably by einstein and mean scientists since einstein. the way we see it is that the regime in which newton's proposals were made and were true, they're still true within that regime. what has changes in a way is the regime, we expanded the regime, so now newton's formulations work as long as you don't travel near the speed of light, but when you begin to travel near the speed of light you have to invoke einstein's theory of relativity. and we do that. our gps devices which send signals to satellites and back at the speed oflight need to be adjusted by einstein's law of relativity to work properly. >> host: albin einstein has stood up. >> guest: albert einstein has certainly stood up so far. although einstein wasn't so sure it would stand up. he had a couple of fudges here and there, which he claimed were one of the biggest mistakes, but

1:49 am

enough at it come back, the cosmological has come back and now seems to be important. so far einstein seems to have stood the test of tine but only been a century. >> host: what is your class called? >> guest: my class is call ignorance as well, and a great treasure to be able to teach at a place like columbia university where they let you have a which is on ignorance and have students enroll. the class started five or six years ago, in 2006, and it was based on my feeling that i was doing students a disservice. i was being a diligent teacher, giving them 25 lectures year in neuroscience, molecular neuroscience, using this textbook -- one of the leading textbooks in the field, but i'm fond of pointing out this textbook weighs seven and a half pounds which is twice the weight

1:50 am

of the human brain. so i think the students get idea by the end hoff the course that everything was known about neuroscience, and that's certainly not true. and that the way we kept track of what we know, build up facts and stick them in these books and that's not true. we don't really know mat much about the brain yet at all weapon don't even know what we don't know about the brain in some ways. we're still finding marvelous things out about it. so i thought, i ought to teach these students the ignorance in neuroscience, so i devoted a couple of lick tours to that at the end of- -- -- lectures to that at the end of the course and decided to see if it worked with other scientist as well. and the course meets once a week, seminar course for hours and i invite members of the columbia faculty or other scientists who are visiting in new york to come in and talk to the students for two hours about what they don't know in a very specific way. not the big questions, not how

1:51 am

did the universe begin of the nature of consciousness, nature and discovery channel do marvelous job on that. these are what i call case histories in ignorance house an individual scientist grapples with this or that, what happens if you know this rather than that, or don't know this rather than that. things of that nature. >> host: who is the scientist you use in the course? >> guest: the book i include four case histories of scientists. in fact, a couple of them are two or theme. one is guy unanimous reese who studies cognitive processes in animal skis start the chapter off by saying is there anything harder knowing whether red is the same to you it's is to me? and i said yes there's one thing harder which is knowing what is in an animal's mind. so the has done some marvelous work with mire roars and dolphins. i should be honest about it and tell you that she is my wife as well.

1:52 am

but she wasn't just a visitor in the class but her work was so marvelous, it's worth highlighting. i highlight three physicists. a highlight a couple of neuroscientists who work in various areas of neuroscience, where there are new question as i bounding we hadn't thought of 0 few years ago, and then i use myself as a case history. that happened because at one class we had a speaker who got terribly ill at the last minute and couldn't make and it i didn't know what to do. and my wife said why don't you be the speaker and i'll interview you. i'll run the class and you be the speaker. so i did and it worked out pretty well, and i have the transport, so i -- transcript about it and i thought i'd use myself as a case history. >> host: how important this money to this research? >> guest: well, how important is money to almost anything? it's extremely important and something we have to think about carefully as a culture, how much money we want to put into research, where we want to put

1:53 am

it, basic research verse applied research and how to make the balance work out. i think the cornucopia of good we have gotten out of research in the 14 generation we have been doing it is a testment to the reason we ooh continue to support it even when we don't know what we're going to get out of it. my favorite parable from benjamin franklin, who witnessed the first human flight, which happened to be in hot air balloons, not fixed wing aircraft it was in paris, a series of balloon flights and human beings lifted off the face of the earth for the figure tile and a spectator says this is fun but what use could this bee and franklin's retort was, what use is a newborn baby? that's a little tough. that's franklin. but he is right, of course. what use is a newborn baby? we don't know but many of them turn out to be quite useful so

1:54 am

we invest in. the, as we should do in science. >> stuart finestein, this is his book, ignorance, how it drives science. there is a web site associated with this book, ignorance ignorance.biology.columbia.edu. >> the author of five previous books, her new book is guest of honor, booker t. washington, theodore roosevelt and the white house din that's right shook a nation. why did this dinner drive the nation nuts? sunrise dinner is a remarkable moment in history that has been completely forgotten and it's because we just don't know about scandals like this. our meter has changed.

1:55 am

when booker t. washington walked up the five steps of the white house he the very first african-american to be invited to sit at the president's table. it had never happened before. african-americans had been invited to meet with presidents in their offices. they had business meetings all the time. but no one ever sat at the president's table, and the nation was outraged. it was really astonishing. >> host: why was he invited? >> guest: well, booker t. washington had a very, very successful working relationship with theodore roosevelt, and they were working together to try to fix the race problem, which was just as much with us, obviously -- obviously in 190 as it is today and they were partnering to try to bring like minded people in into government. and one day roosevelt said to himself, why can't i invite

1:56 am

booker t. to join me for dinner and mix business with pleasure? it was an innocent invitation, and it unleashed just an incredible outpouring of indignation from all over the world, because it had never happened before. >> host: was the president's schedule always public or how did people find out? >> guest: the president's schedule was always public and was covered by some lowly journalist who probably hated this job. it was his job to report that roosevelt had lunch with so and so or a meeting with so and so, and the dinner took place in the evening, and at about midnight, the journalist looked at the president's schedule and probably rubbed his eyes because he saw that booker t. washington had dined with the president. the news went out on the wire, and it was like a thunder clap. it was picked up by every

1:57 am

newspaper, five inch headlines, most of them saying things that we literally cannot repeat today. about why this dinner was such an outrage. >> host: what was the reaction of mr. washington and of the president? >> guest: their reactions at first were bemused. they thought, oh, this is just something that will flair up and will go away. very quickly they realized that was not happening. it seemed that every single person in america had to have an opinion about whether or not the dinner was the right thing to do, and there was some very funny responses. mark twain, for example, who you might thing would have been in favor of the meal, said, absolutely not. the president is just a high-classed tenant at the white house and he has no right to express his personal feelings by inviting a black man to dine there. the reactions fell into kind of predictable sections.

1:58 am

the north was supportive. the south was not. but even the french had an opinion about it, and their opinion was actually, we don't -- we're not amazed that it's the first time. we're amazed it never happened before. so, you can really find a reaction in every newspaper in america, and other parts of the world. >> host: what was in the gist of the dinner conversation? >> guest: the dinner was very innocent. they talked about -- roosevelt has just taken a hunting trip. they talked about their kids. two of the roosevelt children were at the table. it was just a wednesday night at home with the roosevelts, nothing special. and after dinner the gentlemen retired to talk about race, but the dinner itself was just a family evening that was taking place at tables all over america, the same kind of thing. but at this table there was a hot seat. >> host: final question. what was on the menu?

1:59 am

>> guest: the menu has not been recorded but roosevelt loved hot food and plenty of it. so, probably biscuits, comfort food as we know it today. >> host: debra davis, the author of guest of honor, booker t. washington, theodore roosevelt and the din that's right shocked the nation. thank you. >> thank you. >> the first ladies i am drawn for the ones on the ground floor that sort of more modern day first ladies that i can identify with more. people like eleanor roosevelt, jackie kennedy, those are the women whose stories feel close enough to connect with. many of the women in the higher floors on the state floor, they seem like characters from a wonderful story, because it was such a long time ago. it's history and you read a

104 Views

IN COLLECTIONS

CSPAN2 Television Archive

Television Archive  Television Archive News Search Service

Television Archive News Search Service

Uploaded by TV Archive on

Live Music Archive

Live Music Archive Librivox Free Audio

Librivox Free Audio Metropolitan Museum

Metropolitan Museum Cleveland Museum of Art

Cleveland Museum of Art Internet Arcade

Internet Arcade Console Living Room

Console Living Room Books to Borrow

Books to Borrow Open Library

Open Library TV News

TV News Understanding 9/11

Understanding 9/11